Barbara Brown Simmons

Barbara Brown Simmons was the first Black woman to graduate from the UNM School of Law. She was instrumental in the development of UNM’s Black Studies program (now Africana Studies) and the founding several organizations for Black students on campus. She was raised in Texas in the 1950s, and moved to Albuquerque with her family in her teens, attending Valley High School and earning her BA in Political Science from UNM in 1969.

In her interview with Marsha K. Hardeman on May 13, 2016, she discusses her experiences as a child in the segregated school systems of Texas. "Back then," she says, "there were no mixed communities that I was aware of…The only time I saw white people is if maybe I was on the street and I saw them passing in cars."

She contrasts her experiences in the small town of Hereford, in a segregated, makeshift classroom with one teacher for all grades, to her later schooling in the strong Black community of Amarillo. Her first classroom was in the poorly lit basement of the white school in 1954, the same year that the US Supreme Court declared separate schools for white and Black students to be unconstitutional. Upon moving to Amarillo in 1957 at age 10, she encountered "real" Black schools with Black teachers, who taught Black history and Black pride. The teachers were strict and used corporal punishment, but had high expectations and taught that education is invaluable. Barbara loved school and found learning fun.

This experience proved to be a firm foundation for Barbara when her family moved Albuquerque in 1963; Barbara says that was the first time she directly experienced racism, discrimination and hate. She describes witnessing students wearing KKK outfits, which the principal defended as "all in fun." Her teachers used racial slurs, marveled at how a Black student could be so smart, and openly celebrated the rare occasion when a white student got a higher grade than Barbara did.

Upon matriculating at UNM, she enjoyed her freedom from her strict parents. However, she states, "In 1965 when I came to the university, I noticed that Black students were almost like the invisible students. There was nothing for us. Nothing culturally, nothing socially, nothing in the classrooms, no Black history, no Black faculty."

The mid-1960s saw a great deal of anti-racist organizing taking place across the United States, and Barbara had already joined NAACP. She attended a campus event featuring Freedom Ride organizers and observed:

"I don’t want to sound like a racist, but when I went to the meeting, it was all white folks running the meeting. And I don’t care how liberal they tried to be, they really didn’t understand what it was all about in terms of being Black. You know, I just felt like you had to understand from this position what it was to be Black. It was okay for you to be involved, but you don’t understand the way we understand what needs to be done."

These experiences inspired Barbara and others to form the Black Student Union. Predictably, this process encountered obstacles. A Daily Lobo reporter attended the first meeting and, according to Barbara, when the group questioned whether they were "ready for that level of exposure," the reporter "stormed out." A front page article the next day accused the group of telling the reporter to leave.

Internal disagreement was also a factor, specifically whether white students could be members or attend meetings. Barbara recalls,

"Finally we decided as a group our goal is not to separate or segregate, but we felt like as a group that Black people need to get together, define their own agenda, before we bring other people in who we wanted to help us with that agenda and meetings and whatever. But we wanted to organize first."

The goals the group defined were to eliminate racism at UNM and be included at all levels of the university experience.

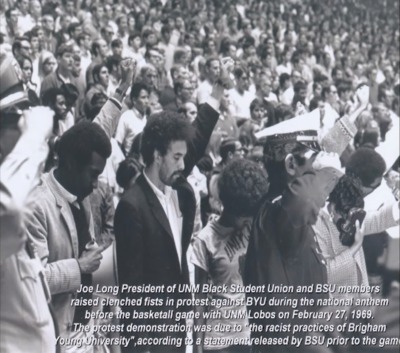

The Black Student Union organized protests against Brigham Young University for its racist policies and practices, inspired by Tommie Smith and John Carlos giving the Black Power salute at the Summer Olympics in 1968. Barbara was arrested for her participation in a protest in 1970 at a UNM athletic event and discusses her thoughts and feelings at the time of her arrest: "That’s when I began to give Martin Luther King and all those protestors all the credit, was going to jail. When they started slamming those [doors], I was so afraid, I could barely breathe…I kept saying, 'are they going to beat me? Are they going to kill me? Am I going to get out of here?'"

The Black Student Union organized protests against Brigham Young University for its racist policies and practices, inspired by Tommie Smith and John Carlos giving the Black Power salute at the Summer Olympics in 1968. Barbara was arrested for her participation in a protest in 1970 at a UNM athletic event and discusses her thoughts and feelings at the time of her arrest: "That’s when I began to give Martin Luther King and all those protestors all the credit, was going to jail. When they started slamming those [doors], I was so afraid, I could barely breathe…I kept saying, 'are they going to beat me? Are they going to kill me? Am I going to get out of here?'"

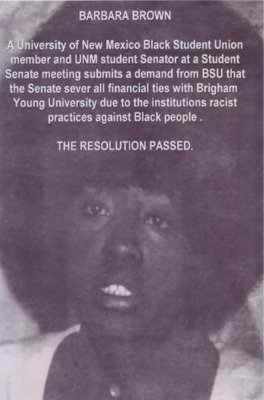

Barbara's activism as an undergraduate also included submitting a successful resolution to the Student Senate to sever ties with Brigham Young University, and writing the proposal called "To Break the Chains" which was the basis of the Black Studies Program at UNM, founded in 1970.

Barbara's activism as an undergraduate also included submitting a successful resolution to the Student Senate to sever ties with Brigham Young University, and writing the proposal called "To Break the Chains" which was the basis of the Black Studies Program at UNM, founded in 1970.

Barbara's arrest played a role later when she attempted to be admitted to the New Mexico Bar. Dean Hart at the UNM School of Law was very supportive and helpful to Barbara during her studies there. Unbeknownst to her, the faculty and administrators who knew her as an undergraduate checked on how the Dean was treating her, because they knew her success would pave the way for other Black students. Ever an organizer, Barbara established the UNM chapter of the Black American Law Student Association, with a membership of one, and sponsored the BALSA regional conference at UNM during her time at the law school. After two devastating failures, Barbara passed the bar exam, but faced a hearing with the Ethics Committee about her arrest as an undergraduate, which she navigated successfully.

After an early experience working with legal aid at the South Broadway Community Center, Barbara decided to pursue criminal defense. She felt everyone was entitled to fair defense representation, but also observed that clients were more able to pay for criminal defense than, for example, family law. She worked for 25 years as a criminal defender in California, accepting all kinds of cases from jaywalking to murder one. After her long career, Barbara concluded that the criminal justice system is "racism 101" and became disillusioned about creating change because of the embedded nature of racial discrimination. Community involvement seemed more promising to her, and she took on pro bono work with homeless veterans and ran programs for the United Negro College Fund, with the goal of increasing students' self-esteem and encouraging them to stay in school.

Barbara believes that the stereotype that young people don't care is untrue.

"I hope one day we don't have to say Black Lives Matter, I hope all lives matter, but I think there is a reversal of a lot of things that we have accomplished, and I do think we are back on the firing lines. I do think people that have all this education, who don't have to worry about jobs being taken [away], I do think it is our obligation to go back out, get involved with the youth, not as leaders but as supporters."

Barbara ends her interview with an inspiring and necessary message characteristic of her lifetime of hard work, achievement, and persistence in the face of adversity:

"I hope that anybody who listens to this interview understands, we all have an obligation. We all should be committed, black, white, green. Because if you can stop hatred here, you can stop hatred here…We just need to stop hate."

Sources

Anthony Louderbough Pictorial Collection, Center for Southwest Research, University of New Mexico

Written by Amy Winter