Suffrage Was Not Equal

A Continued History of Disenfranchisement

The history of United States voting rights is complicated by its history of racism, sexism and classism. By middle of the 19th century, most abolitionists and suffragists publicly supported equal rights for all. As the Civil War progressed and during Reconstruction, the two groups struggled to find a political strategy to gain universal suffrage. Some thought that seeking suffrage for both women and black men at the same time would not result in any gains in voting rights. Most women disagreed.

Many early suffragists began their civil rights work as abolitionists. Susan B. Anthony, Lucretia Mott, Lucy Stone and Elizabeth Cady Stanton were notable examples. Alongside abolitionists like Frederick Douglass, these women founded the American Equal Rights Association (AERA) in 1866 “to secure Equal Rights to all American citizens, especially the right of suffrage, irrespective of race, color or sex.” The group only existed for three years when disagreements over prioritizing Negro Suffrage over Women's Suffrage tore the organization apart. Leaders on both sides took opposing positions positing their cause as more important than the other's. Some abolitionists engaged in anti-womens-suffrage campaigns and rhetoric. Likewise some womens suffrage leaders, Stanton and Anthony in particular, made classist and racially charged statements and enlisted racist supporters to promote their cause. Actions, speeches and writing on both sides gave rise to ill will and anger which plagued the fight for womens suffrage long after African American men recieved the vote with the 15th Amendment in 1869.

After 1869, there continued to be dissension and division. While the fight for suffrage gained momentum and was won, Jim Crow laws and the rise and influence of the Ku Klux Klan restricted African American’s ability to vote and act as full citizens. Other efforts restricted voting rights for Native American and Chinese American communities after women received the vote. It was not until the Voting Rights Act of 1965 that federal laws mandated true universal suffrage in the United States. Even with these laws, recent elections have made clear that there are still significant voting equity and inclusion issues today.

The difficult history of women's suffrage and racism has not always given due credit to many people who have contributed to the fight for equal voting rights. Below are some of the men and women who less well known for their important contributions.

Nannie Helen Burroughs was a leading suffragist, educator and president of the National League of Republican Colored Women. She is also known for founding the National Training School for Women and Girls in 1901, a school funded by the African American community and designed to educate women in a wide range of academic and vocational courses. For more information, visit this National Park Service biography.

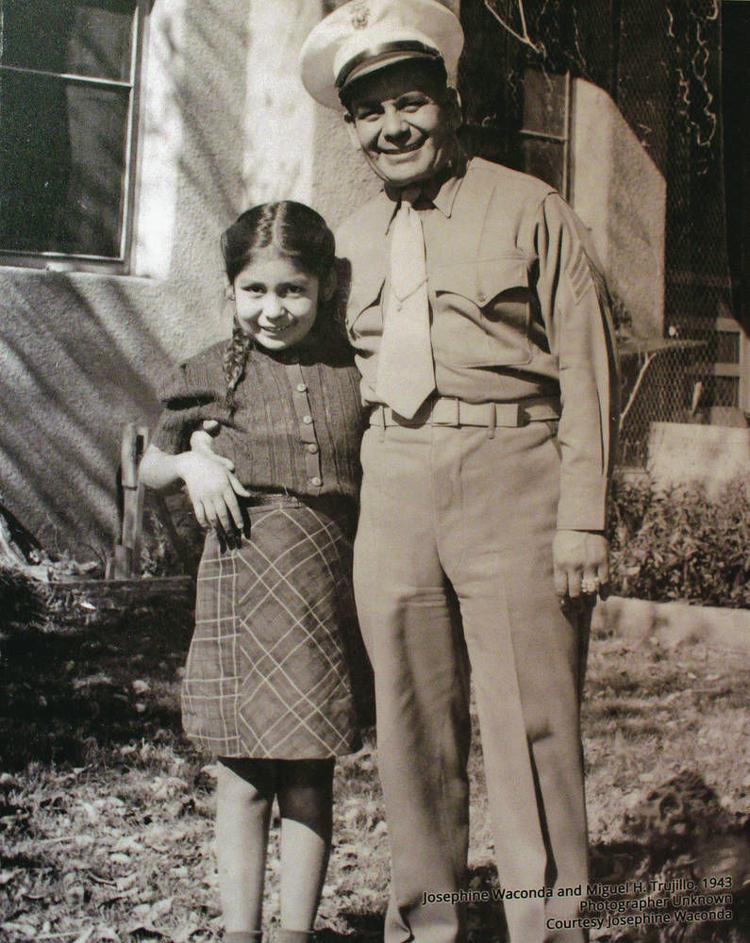

Pictured to the left is Miguel Trujillo with his daughter Josephine T. Waconda. Trujillo, a resident of Isleta Pueblo, returned from serving in WW II as a Marine and was denied the right to register to vote based on a provision in the New Mexico State Constitution. Although officially United States citizens as of the Indian Citizenship Act in 1924, Native Americans who lived on reservations and did not pay state taxes, were considered ineligable to vote. Trujillo sued and won with the state finding that the New Mexico constitution vioated the Fourteenth and Fifteenth Amendments and discriminated against Native Americans on the basis of race.